I can see him onstage, strumming on his guitar, but I can’t keep my eyes open to watch the scene. In a handful of instances, and with the help of hospital records detailing specific instances, she attempts to recreate what might have been going on in her feverish and struggling brain. Friedman embraced him, my dad broke down, a brief surrender.” It will take time, but she will improve.’ When Dr. Even so, he looked my dad directly in his eyes and said, ‘Please stay positive. “That picture contrasted sharply with the disarrayed young woman Dr. In this short video interview, she discusses how strange it was to watch that old footage, that “other Susannah” in the hospital video footage, to try to reconcile the fact that it was her, but what part of her was that exactly.įrom her father’s journal, she can assemble scenes like this:

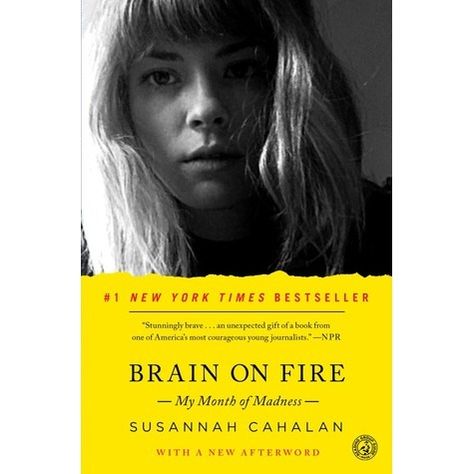

Her thoughts are incomplete, seemingly unrelated, hallucinatory: the reader has a tactile representation of what her brain was like in these earliest stages. “Now, years later, these Word documents haunt me more than any unreliable memory.” When she became increasingly unstable and openly troubled, her father suggested that she try to write out her thoughts, and excerpts from this computer diary add another dimension to the drama. As I stumbled to the bathroom, my legs and body just wouldn’t react, and I felt as if I were slogging through quicksand. “When I got to my feet, a sharp pain lanced my mind, like a white-hot flash of a migraine, though I had never suffered from one before. Some of what she remembers from before she was admitted to the hospital seems coherent and clear, the earliest stages of feeling unwell. And Susannah Cahalan, with her journalist’s training, shapes it into a compelling and sleek narrative.Ī writer’s brain might be a primary source for other memoirs, but Brain on Fire must rely on interviews with doctors and nurses and friends and family, medical records, video footage, the hospital journal that her divorced parents used to communicate, her father’s personal journal, as well as her own notebooks and remembrances. This bizarre and painful experience translates into a memoir with an inherently thriller-like pace and subject. Her editor approved the pitch for the article “My Mysterious Lost Month of Madness,” for which she won the Silurian Award of Excellence, and this article would become Brain on Fire. The story of her recovery is just as shocking. What was not only surprising, but completely shocking, is that only days later, she would wake in a hospital bed, with no memory of having gotten there, with her condition rapidly deteriorating into catatonia. Yet, the three story pitches she has just volleyed to her boss have flopped. She wasn’t surprised she was completely unprepared for the meeting.īut what she did not realize was that that failed meeting was just one of a string of uncharacteristically chaotic and disjointed events which occurred as part of her “descent into madness”. She started as a “copy kid” at the New York Post, sorting mail and making coffee, and when readers meet her on the page, she is a full-time writer there.

#BRAIN ON FIRE NOVEL HOW TO#

Susannah Cahalan knows how to tell a story.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)